Though

he may flourish among his brothers,

the east wind, the wind of the Lord, shall

come,

rising from the wilderness,

and

his fountain shall dry up;

his spring shall be parched;

it

shall strip his treasury

of every precious thing.

~Hosea

13:15 (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.)

In other words, don't mess with the East Wind. And speaking of brothers, what in the world does he mean when he says "the other one"?

After the highs of the first episode, and the lows of the second, I really wasn't sure how to approach His Last Vow. I shouldn't have worried. It's a really tightly scripted episode, with impeccable pacing and a bundle of surprises, if somewhat lacking in dramatic tension compared to last season's finale. There shall be spoilers.

Sherlock

has always, really, been about three things: power, love, and truth—and how

they interrelate. His Last Vow brings all three into play, illustrating the show's vision and how it has changed. Must love obscure the truth? Is information the only form of power? Is truth naturally hostile to love?

Kaitlyn Elisabet Bonsell observes in a Breakpoint article that in A Scandal in

Belgravia, Sherlock despises Irene’s use of sex for power. He scoffs, “you cater to the whims of the pathetic and take your

clothes off to make an impression. Stop boring me and think. It's the new sexy.” According to Sherlock, mental prowess is a much more effective form of influence, and Irene's use of sexual attraction to shock is more than just immature, but boring. (Thoroughly agree—Miley Cyrus is such a reactionary.)

Bonsell also observes that John is really trapped in the same way of thinking as Irene, with his endless succession of identical girlfriends. The most meaningful relationship in the series up to that point—that of Sherlock and John—had nothing to do with sex (yes, shippers—get lost), but a loving bond between friends. “Caring is not an advantage, Sherlock,” says the Machiavellian Mycroft. At the end of Scandal, Irene’s plan is destroyed by the weakness incipient in her form of power: love.

His Last Vow has made it clearer than ever that

caring is not only not an advantage,

but it is actually a disadvantage. When, in The Empty Hearse, Sherlock returned after two and a half years of freelance crime-solving abroad, the dramatic change in his character seemed unprecedented. However, we soon realize that John’s voice still echoes in his head, among

all the other deductions, critiquing his actions from afar, acting as his

conscience. Sherlock has, in fact, started to see the truth not just about

everyone else’s weaknesses and foibles, but also about his own. While he spoke a

lot about not letting emotion interfere with observation, his own pride very

much obscured his vision.

His Last Vow has made it clearer than ever that

caring is not only not an advantage,

but it is actually a disadvantage. When, in The Empty Hearse, Sherlock returned after two and a half years of freelance crime-solving abroad, the dramatic change in his character seemed unprecedented. However, we soon realize that John’s voice still echoes in his head, among

all the other deductions, critiquing his actions from afar, acting as his

conscience. Sherlock has, in fact, started to see the truth not just about

everyone else’s weaknesses and foibles, but also about his own. While he spoke a

lot about not letting emotion interfere with observation, his own pride very

much obscured his vision.

Yet

despite this refreshingly redemptive turn, Sherlock's character development

comes at the expense of his mind. The advent of Charles Augustus Magnussen

brings that fact to the forefront, in the smashing season finale of season

three.

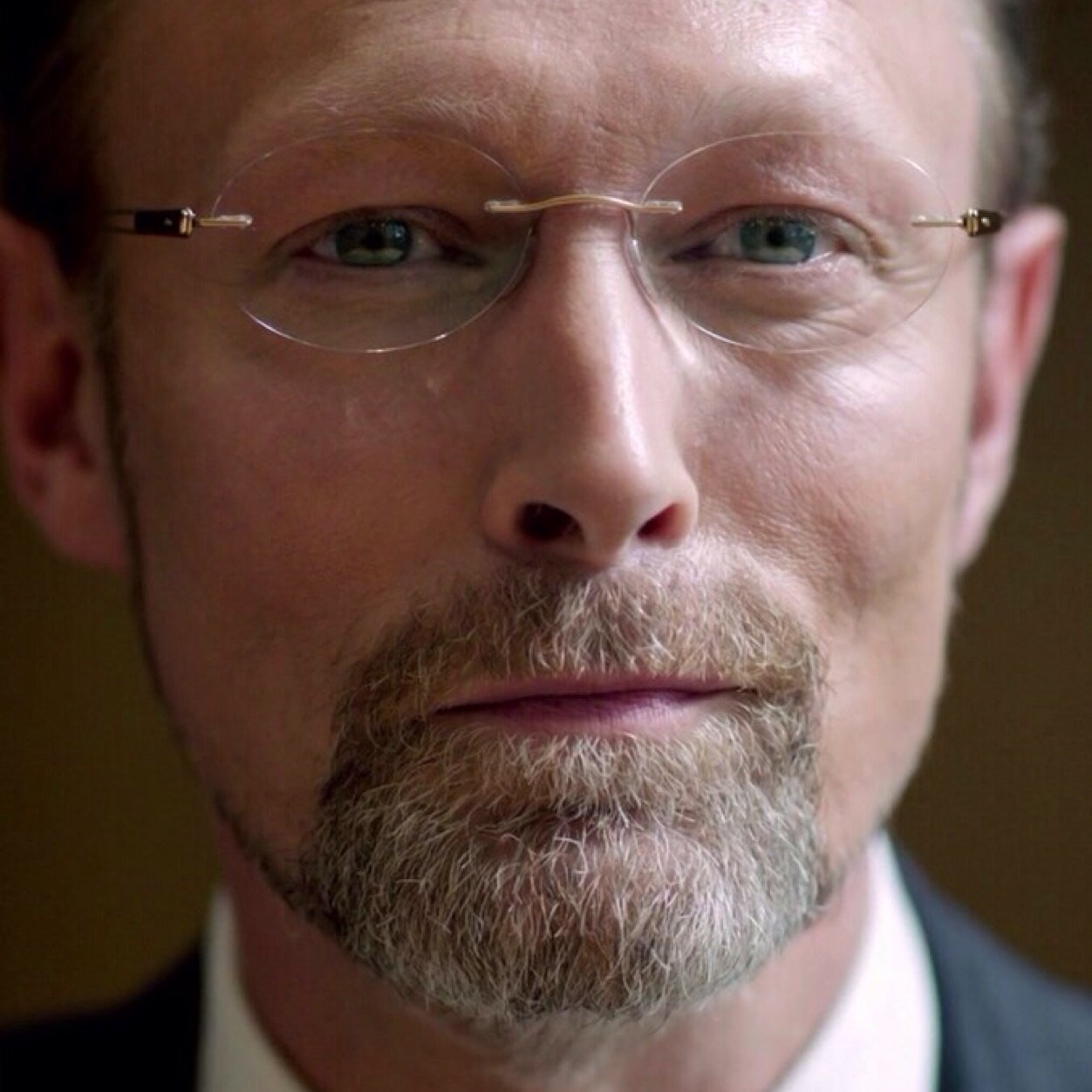

Speaking of which, what of our new villain? Andrew Scott was always going to be hard to beat. Now we get to see Britain's favorite heartthrob up against the brother of Denmark's favorite heartthrob, a novel situation at the least, but emerging as one of the best antagonisms in the show so far. Charles Augustus Magnussen, a Danish take on the original Milverton, is a bold reimagining of Conan Doyle’s sleazy blackmailer. Lars Mikkelson is simply a phenomenal antagonist, equal parts creepy, vulgar, smooth, and unpredictable. From the first few minutes, we are fascinated by his cool under-acting and easy sense of dehumanizing power. The fact that his insults are so petty make them all the more effective; he doesn't care enough about any human being to grant them the dignity of real rivalry. Knowledge is power; information is ownership.

And yet, he's not really given his chance. Halfway through the episode, his quickly escalating sense of villainous grandeur is nipped in the bud by three people breaking into his “secure” offices simultaneously (plot hole!), whereupon we quickly have a shocking but somewhat unsatisfying showdown, and an overlong excursion into the maze that is Sherlock’s mind palace. More on that, later, but the point is: this abrupt shift of focus robs the more than competent Mikkelson of a chance to completely flex his thespian muscles. Bringing Moriarty back to life in the very same episode makes this even worse.

While there's plenty of chatter about Magnussen's control of the entire western world, and several really classic scenes where he demonstrates this by, shall we say, violating personal space, he doesn't actually get to acquire Moriarty's air of omniscient, Big Brother authority that made Sherlock’s arch-nemesis so terrifying in The Reichenbach Fall. Where is this power? Where are the guys with machine guns? Let's have a little show and tell, here.

And yet, he's not really given his chance. Halfway through the episode, his quickly escalating sense of villainous grandeur is nipped in the bud by three people breaking into his “secure” offices simultaneously (plot hole!), whereupon we quickly have a shocking but somewhat unsatisfying showdown, and an overlong excursion into the maze that is Sherlock’s mind palace. More on that, later, but the point is: this abrupt shift of focus robs the more than competent Mikkelson of a chance to completely flex his thespian muscles. Bringing Moriarty back to life in the very same episode makes this even worse.

While there's plenty of chatter about Magnussen's control of the entire western world, and several really classic scenes where he demonstrates this by, shall we say, violating personal space, he doesn't actually get to acquire Moriarty's air of omniscient, Big Brother authority that made Sherlock’s arch-nemesis so terrifying in The Reichenbach Fall. Where is this power? Where are the guys with machine guns? Let's have a little show and tell, here.

Poor John Watson, can he never get a moment's rest?

After

this point, the episode quickly spirals into one of the darkest episodes of the

series yet, a complete change from last week's bundle of sentimentality. Mary

Watson is, it turns out, a ruthless ex-assassin who's not so ex. It's quite an

emotional challenge to the pair who have played a loving couple for the entire

season, but Amanda Abbington and (of course) Martin Freeman both deliver

phenomenal performances in their own personal Hosea and Gomer story.

I'm torn. This is the first of two huge creative decisions made in His Last Vow. Like the introduction of Mary in Sherlock's absence, this once again upsets the entire balance of the show, and I'm not entirely sure I like that. Watching it the first time, it's impossible to judge, being swept up in the stylishness that is Sherlock, but on reflection, despite the excellent delivery of the story-lines, I'm not quite sure I approve of the writing. I'm not such a devotee of Sir Arthur as to demand the level of faithfulness in, say, the Jeremy Brett Holmes adaptations, but it's starting to get a little ridiculous.

| This picture may be one of my new favorite things |

But then we have...

...a young Watson? Mary Morstan: Tomb Raider? Sherlock on a killing spree? Moriarty: Night of the Living Dead? As Steven Moffat himself commented "At

some point, don’t you think they’re going to sit in 221B and say ‘Nobody ever

dies! How are we supposed to investigate murder if they all get up again?'"

Too late. It's starting to feel a little like self-congratulation and creative laziness. But that doesn't make sense—if they can invent someone as awesome as Magnussen, why return on a Greatest Hits victory lap by bringing back Andrew Scott? I am still holding out, somewhat desperately, to the theory that this may be one of the other Moriarty brothers. (But let's face it, that would be just as corny.)

Too late. It's starting to feel a little like self-congratulation and creative laziness. But that doesn't make sense—if they can invent someone as awesome as Magnussen, why return on a Greatest Hits victory lap by bringing back Andrew Scott? I am still holding out, somewhat desperately, to the theory that this may be one of the other Moriarty brothers. (But let's face it, that would be just as corny.)

More

distressing, in some ways, is the choice to alter Mary's character. It was

beautifully executed, yes, and the only time Sherlock has moved me to tears, but a

little manipulative. Come on, just because she is more than usually bright (I'm

no intelligence agent, but that skip code was *cough* elementary), has a good

memory, and is, in general, a strong female character, she has to be given a

tragic background? Why, in particular, are married mothers not allowed the

privilege of intelligence? I loved the fact that she was such a classy,

ordinary person. It just furthers the season three theme that to be a loving

person, to be caring, is a disadvantage. Ruthlessness is an asset. Sherlock

cares, and he's losing his mind. Mary is smart, and she's a cold killer.

However,

my critical annoyance is starting to fade as it all starts to feel inevitable.

Freeman and Abbington really are very good. Cumberbatch is, as always,

impeccable. Lestrade, Molly, Mrs. Hudson, and Anderson all make decent cameos

(the last an unusually long one).

Once

we have gracefully extricated ourselves from the emotional fallout of the Mary

revelation, Magnussen once again looms on the horizon. Because of all that's

going on, the tension has somewhat suffered, and the climax itself felt a little

underwhelming. It is here that Sherlock's lack of cleverness comes to the fore.

He's already made some serious mistakes this season, among them ignoring his

instincts when it came to Mary, but his motivations for forcing the showdown

with Magnussen, his subsequent bewilderment and lack of focus, and his

ultimate, clumsy solution felt paper-thin and completely out of keeping with

the Sherlock Holmes character. If we'd been given an impression, however weak,

that Sherlock was planning something, it would have worked—if we (and Sherlock) hadn't been clued in that Magnussen's vault was inside him, the

reveal would have been more dramatic.

I

don't think that Sherlock Holmes would object to the murder of Magnussen (of

course, he originally approved it), especially as it is in defense of the

vulnerable, but the way he goes about it feels far too much like the James Bond character Benedict Cumberbatch is becoming.

On the roof of St. Bart’s, Sherlock and Moriarty were both crippled by their respective weaknesses. Sherlock proudly believes in cleverness, and was fooled into thinking Moriarty’s master plan involved a code to unlock nuclear weapons. Moriarty, on the other hand, realized that while Sherlock may be be allied with forces of goodness, he was perfectly prepared to be a law unto himself. Sherlock loves, but he won’t allow it to get in the way of his purpose: solving crime.

| After THAT who couldn't hate this guy? |

Then there's the conundrum that "Caring is not an advantage." Sherlock obviously cares. Like the Holmes of Conan Doyle, he is always denying this (frequently describing himself as a "highly-functioning sociopath," even as his actions disprove the fact), but the thing is, I don't think caring has to be a disadvantage. It is only ever a disadvantage if it is built on a lie. As that great group of contemporary philosophers, The Black-Eyed Peas, observe, "If you've never known truth, then you've never known love."

And Sherlock's problem, an unusual one, from one so devoted to truth, is that, to quote again from Steven Moffat, "When

he gets emotional, he gets blind. He doesn’t spot Mary as a fraud as he should

have...Ages ago, he should have spotted it...When he first meets her there’s a whole blizzard of words and one of

them is 'liar' and he ignores that word because he wants to like her."

So to summarize: my three issues are Mary, Sherlock, and Moriarty. Respectively, my solutions:

Solution: Let Mary continue to be the house-wife. Don't let the assassin past be a big deal. She doesn't need to be Katniss to be

interesting, and I think this decision actually weakens, not strengthens, her

character. Her strength is of a different sort, a sort which does not require her to be macho.

Solution:

Steven Moffat should read The Abolition of Man: "The heart never takes the

place of the head: but it can, and should, obey it." Sherlock's character

is also weakened by his allowance of his emotions to rule his reason. It

doesn't seem very likely from him. Like Janine, I'm charmed by Sherlock, but

"You shouldn't have lied to me. I know what kind of man you are."

Solution:

Just kill him, why don't you?

But

now I've ranted, I have to admit that I kind of loved this episode. I will be watching it for a third time. It moves

along at a cracking speed, with a strong thread of humor to offset the

darkness. The music is gorgeous—the mind palace sequence is stunning (if a

bit long)—the villain is creepy—the sets are evocative—the acting is

stellar—the plot is unexpected and clever (mostly)—the dialogue is

believable.

John’s

decision to forgive Mary was a fine one. While it still seems their

relationship is based, somewhat, on refusing to look the truth in the eye, I

believe the decision he made was not for his own peace of mind (after all, in

those six months, he must have imagined secrets even more horrible), but for

hers. Mary was wrong—the truth did not break John Watson. Caring doesn't have to be a disadvantage.

While

it did go on a bit, I really enjoyed the Sherlock mind palace sequence, as it

brought him into close contact with his demons (let’s just leave Jim there, shall

we?) and true motivations in a stunning bit of cinema. And the music, gosh, the music.

Overall, it is a fine contribution to a series which is already one of the best things on television (and pretty much better than anything in theaters), and while it has its flaws, they are most noticeable when comparing it to itself, when viewed in the larger context, and as heralds of things in season four. Heck, season four can take care of itself. I'll probably revisit this review and touch it up, once again, but in the meantime, I give this episode...

4/5 stars

Hannah Long

No comments:

Post a Comment

Warning: blogger sometimes eats comments - make sure you copy your message before you post.